In Langston Hughes’ beautiful, profound poem “Theme for English B,” a young man, the only Black student in a college English course, sits down in his rented room at the Harlem YMCA to write an assignment given him by his white professor. He’s struggling with the teacher’s instructions, which tell him to write a single-page essay, and to “let that page come out of you. Then, it will be true.”

As he puts pen to paper, the young man in the poem realizes that the pronoun “you” may mean something more complicated than the instructor assumes. In the poem, he writes as an individual, telling the instructor of his likes and preferences: “I like a pipe for a Christmas present / or records—Bessie, bop, or Bach.” But he also realizes that his page will also be the product of his identity and experience as a member of a particular group—in this case, Black Americans.

Given that none of us lives outside of history or outside of the structures of our society, this will be the case whether he intends it or not. He’s just not sure that the instructor will understand what he’s getting when he reads the theme. Here are the lines that seem to me crucial:

So will my page be colored that I write?

Being me, it will not be white.

One gets the sense that the young man is a little uncertain of his footing; he seems to suspect that what he writes will not be what the instructor is looking for or expecting, for reasons having vaguely to do with their difference in race. Still, he forges ahead:

But it will be

a part of you, instructor.

You are white—

yet a part of me, as I am a part of you.

There are two profound ideas in these lines. They are in tension with one another, but that tension doesn’t mean that they contradict each other or that one makes the other less true.

I think most readers find the idea in the second of these two quotes more attractive and understandable—that is, the idea that the young man’s “page” of writing can bridge the various barriers of race, age, class, and educational experience that exist between him and another person–in this case, his instructor. This is basically the claim I and many other English teachers make for the power of poetry and of imaginative literature in general.

But, despite the fact that I believe this, it’s too simple and easy to ignore the more difficult lines that precede it. For right now I want to focus on those lines, which have to do with whether the speaker’s identity as a member of a particular group (not just as an individual) will or should come through on the page. That’s a more complex and challenging proposition to some of us, I think. Some of us might ask ourselves, “So why bring race into it?”

And Hughes’s young man might answer, “Because I can’t keep it out and still be honest about who I am. If I leave it out I’m not being true to what I and others like me have experienced or have loved or have dreamed of.” And what’s the point of writing—whether it’s a theme for English B or a poem or a graphic novel or whatever—if you’re not going to be true to the experiences, the history, the values, and the aspirations you share with others like yourself?

Hughes’s point, here and in some of his other writings (his 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain”), may be more intuitive to us if we try to understand it as a more general rule, and not as unique or particular to the vexed legacy of racism and racial conflict that is so much a part of our ongoing history in the United States.

The point is really simple: as writers we express ourselves both as individuals and, consciously or not, as bearers of whatever forms of culture and community have imprinted themselves on our identity–family, church, school, state, neighborhood, ethnicity, gender, and, yes, race. Hughes was not the first, and would not be the last, to assert that part of being true to oneself as a person and an artist means also being true to where one comes from, specifically the values and culture of the community in which one was raised. The extent to which we speak or write as individuals or as “bearers” of a group identity varies from situation to situation, and, in the case of poets, from poem to poem. But I’d like to play this out in a little more detail so we can see some of the considerations that go into this proposition.

There are three basic dimensions to any poem. It’s usual—and correct, I think—first to view the poet as trying to create something unique: to give the reader an experience he or she could not get elsewhere, from any other poem or poet. We might be tempted to call this the personal dimension of the poem; but the poem’s uniqueness does not or should not depend on the details of the writer’s unique autobiography. It doesn’t really matter if the poem comes out of the writer’s imagination or out of his or her experience. (Poe probably never met up with a raven who kept crowing “Nevermore,” but that poem is still an experience we can’t get anywhere else.) The point is for the poem to create that movie or picture in our minds that is unique to the poem.

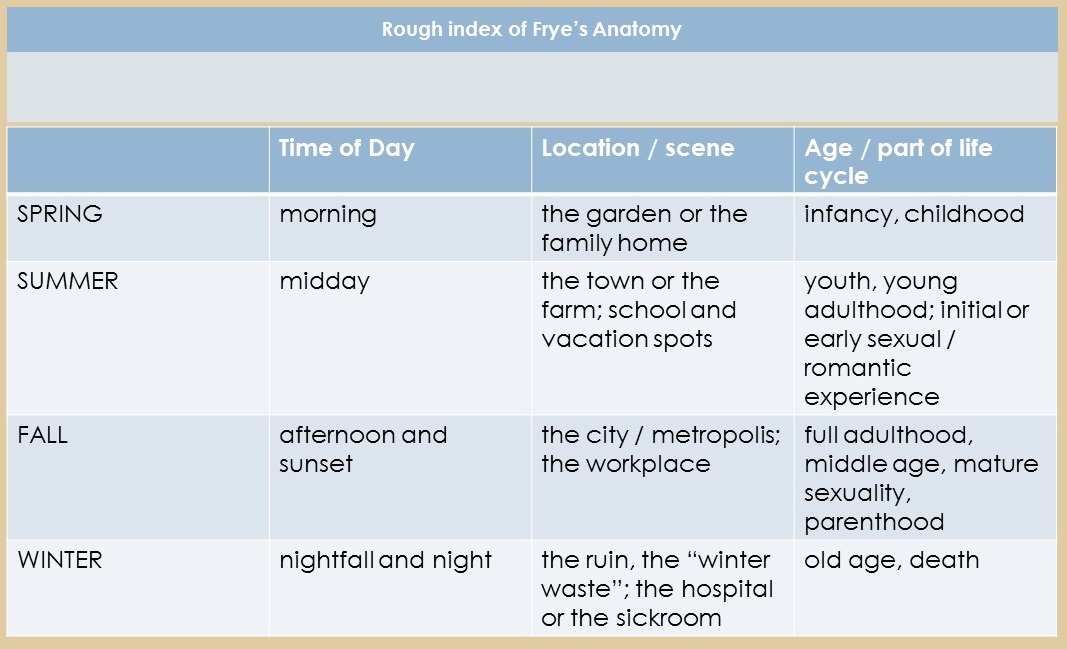

At the other end of the scale from this personal aspect is what we might call the universal, those patterns of meaning that encompass human lives across the board. (Frye’s anatomy of the seasons is one attempt to describe what this aspect looks like.) This is the framework that allows us to connect with and identify with unique experiences other than our own, even though we might be distant in time, place, and culture from the poem’s scenario. This is the inner voice that allows us to say, when reading a poem like Tony Hoagland’s “History of Desire,” yes, that’s what it feels like to be 17 and in love; or, reading one of Li-Young Lee’s beautiful but sorrowful reminiscences of his dead father, yes, that’s what it’s like to mourn a loved one. We don’t have to be from a small town in Indiana to “get” what’s happening in Hoagland’s poem; nor do we have to understand the particular Asian-American family dynamics that hover in the background of Lee’s evocative images to identify with his feelings of loss and love.

But in between these two dimensions of the poem there’s a middle one that’s worth considering. Sometimes the poem’s meaning or significance is influenced by the poet’s writing from within a particular community. This is the “voice” we hear in our heads when something in the poem tells us the speaker is not just speaking as an individual, but is speaking as a member of that particular group: speaking for instance as “a Black person,” as “a woman,” as “a member of Generation Z,” or even (in light of recent events of February 2022) “as a Ukrainian-American.”

The boundaries and territory of that community can be defined in a variety of ways. But most commonly and powerfully it has to do with the way in which a specific group’s history and culture have distinctly shaped that group’s identity, its outlook on life, and its way of expressing itself. This distinctiveness might have its origins in common ethnic, cultural, or racial experiences and identifications; in religious traditions; in experiences or ways of thinking that are gender- or class-specific; in generational divisions; or perhaps others I’m not able to think of right now.

Stephen Henderson, in an important little book called Understanding the New Black Poetry, coined the term “saturation” to describe the source of that sense that we have, when reading a poem or short story, that the voice we are hearing is speaking in the way I’ve alluded to above–not just as an individual or as a generic human being, but as a member of a particular group whose orientation to the world or experience in the world is distinct from that of other groups in some significant way. I like the term “saturation” because it suggests that what Henderson is talking about is not like an off-or-on switch; it’s something that occurs on a scale. Some poems are more “saturated,” if you will, by the particular group identifications of the speaker or the author; some may seem to lack this “group” dimension altogether.

Henderson noted that this “saturation” can be felt in at least three ways: in ways of speaking (vocabulary, grammar, idioms) that are distinctive to the group; in the choice of images (either literal or figurative) that draw on the distinctive history, culture, or experience of the group; and, finally, in the implicit orientation to the world (belief and / or value system) that is characteristic of the group. The more instances of any of these we encounter in a given text, the greater the “saturation.”

That’s not to say that anyone who personally identifies as Black, female, Catholic, trans, Ukrainian-American, or whatever is going to write in an obviously particular way; the “saturation” factor in a particular poem my be greater or lesser, depending on the story or the portrait the writer is presenting. Even Langston Hughes’ young man in “Theme for English B” stops short of saying his text will be “Black” because he’s a Black man; he only knows it will “not be white,” and that “it will be me.” But in other poems Hughes increases the “saturation” quotient in precisely the ways Henderson describes: using language that is more firmly in the style of African American everyday speech of the day; referencing Black musical forms like jazz and blues; and voicing the specific political, social, and cultural aspirations of his community. (See his poem “Dream Boogie” for an example of what I’m talking about here.)

I’d like to talk about one more of Henderson’s ideas, that of the “mascon image.” Although it’s only one subtopic in Henderson’s overall discussion of this “saturation” idea, I’ve found that it helps us think more clearly about the ways in which poems can give voice to the experience of a community or a people as well as that of the individual poet.

Henderson noted that communities of human beings can be distinguished by the particular meanings that a given group attaches to certain objects or images. Because of their associations with the shared history or current life of the group, these images or objects have over time acquired powerful and complex emotional charges. Henderson labeled these “mascon terms” or “mascon images” (“mascon” being a term he adapted from communication theory, a shortening of the phrase “massive concentration”). He pointed out a number of such terms that he thought important to an understanding of the Black experience and poetic tradition—trains, trees, ships, rivers, for instance.

I won’t take time here to discuss the particular mascon terms Henderson linked to the African American experience, though I think that would be a worthy pursuit. For the moment I want to use his discussion as a jumping-off point for a broader understanding of his meaning. Based on other discussions we’ve had, I think we can see that Henderson’s “mascon term” is closely related to the concept of a “conventional symbol.”–but a very special and powerful instance of that category, not limited to Henderson’s specific focus on Black poetry.

Let’s take for an example the image that is probably the primary “mascon object” in Christianity—the cross. In the beginning this object was just another tool of capital punishment in the Roman-occupied Palestine, meant to send a vivid message as to what happened to you if you crossed (pardon the pun) the Empire. Most folks of that time and place just thought of it the way we today might think of the electric chair.

But the early Christians adopted the figure of the Cross, and the story of Christ’s crucifixion as a sign of their identity and belief system, and thus made it into something deeper and more complex–a “mascon term,” in Henderson’s terminology. For them it has become a kind of visual shorthand for an entire theology. It at once symbolizes suffering and victory, death and resurrection; it serves as a sign both of believers’ guilt as sinners and their glory as redeemed children of God. It’s all this and more, and all a Christian has to do is see the shape in a particular context to call forth all of these meanings and the feelings associated with them.

As a result, it seems reasonable and natural that a poet working in Western literary tradition, deeply informed as it is by Christianity, would find this particular image useful, maybe even natural, to a faithful rendering of his or her experiences and feelings. The community of Christians is defined by their mutual and shared recognition of the Cross and other trademark “mascon terms” (water, bread, wine, and other sacramental substances for instance). Such shared cultural resources both distinguishes them as a group from others and knits them together as a community.

Obviously readers outside of, or unfamiliar with, the culture of Christianity, may sense that an image like the Cross is somehow significant when they encounter it in a poem. But they may have to unpack it more slowly and consciously, using research or other contextual clues, to make sense of it. They might read as “outsiders,” so to speak, but that doesn’t make the facts or the feelings of the poem impossible to understand. Using a combination of a little research and their own powers of sympathy, empathy, and imagination, they can “translate,” and successfully create the “movie in the mind” that the poem wants to convey to us.

I’d like to loop back to my beginning point. I believe that the job of any poet (any artist, really) us to give us an experience that shows us we’re not alone despite the solitary uniqueness of our individual lives. But I also believe that the work of the poet (or of any artist) is not just an individual product, but is also a product of the culture, tradition, and community in which that artist’s talent was formed and developed.

I know for instance that, when I write poetry, I write differently—in imagery, in word choice, in worldview, etc.–than I would had I not been raised where I was: in a tight-knit German Catholic community in a small town in Indiana. Yes, my poems are my words, they come from “what I feel and see and hear,” just like Hughes’s narrator in the “English B” poem. But he sees and feels and hears Harlem, and the North Carolina of his youth–a different set of inputs than my home town and home culture. And like him, I can’t help that my page is “colored” by where I come from. And neither of us would have it any other way.

And that’s basically what Hughes’s young man in “Theme for English B” means when he says of his own page, “Being me, it will not be white.” He can only be himself, and his race and his community and his people’s history and culture are part of who he is. And yet his distinctive experience and culture as a Black person doesn’t necessarily prevent him from being heard or understood by his white professor. His page still “will be / a part of you, instructor”–because “You are white– / Yet a part of me, as I am a part of you.”

That instructor might have to listen a little bit harder; he might have to process what he’s hearing more thoughtfully than he might with someone of his own race and class cohort. But if he does, he will feel more connected, and more human—even if, as in Christians’ contemplation of the Cross, that connection may bring pain and guilt as well as joy and redemption.

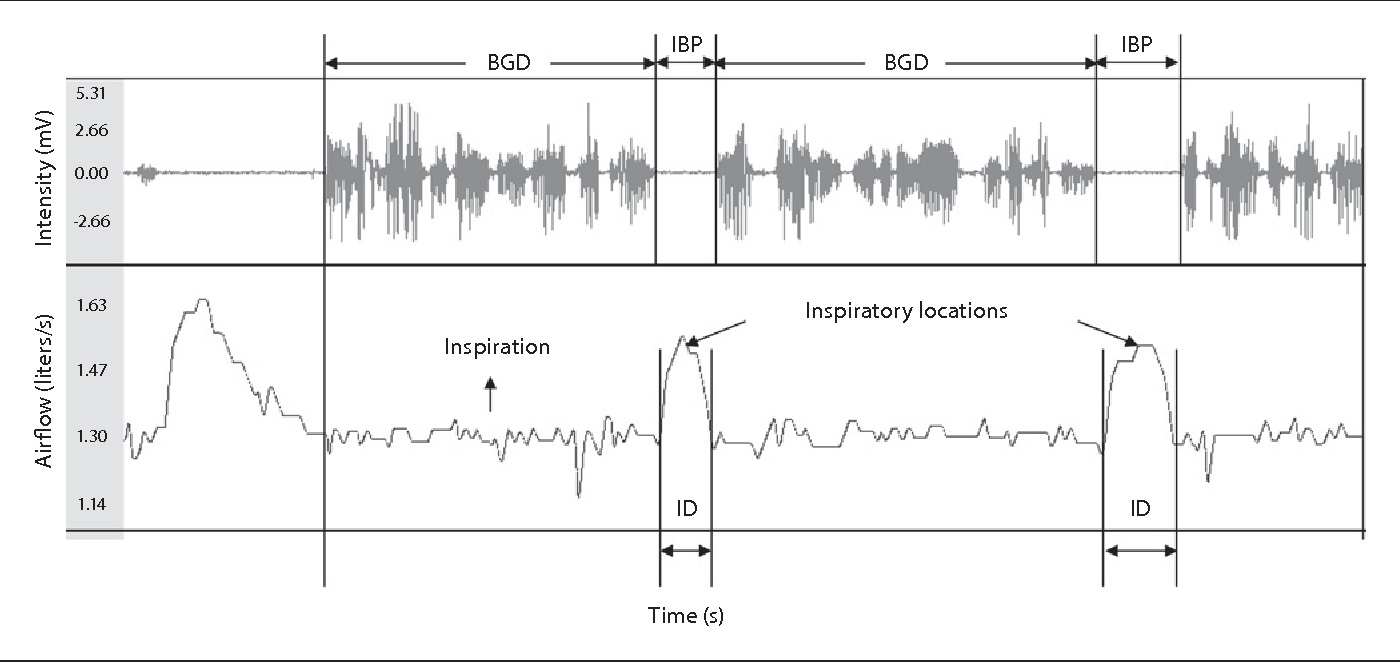

When I hear others read poetry aloud I am often fascinated by the choices that they make about where to take a pause for breath. This is true whether I am listening to a poet read his or her own work, or it is someone in a poetry course reading a poem that he or she is seeing on the page for the first time. There is no real rule about where to pause in reading a poem out loud, but I think it is instructive to consider the possible factors that drive this choice. For instance:

When I hear others read poetry aloud I am often fascinated by the choices that they make about where to take a pause for breath. This is true whether I am listening to a poet read his or her own work, or it is someone in a poetry course reading a poem that he or she is seeing on the page for the first time. There is no real rule about where to pause in reading a poem out loud, but I think it is instructive to consider the possible factors that drive this choice. For instance: